From UC Santa Cruz News

Climate change sends tropical species racing to higher elevations, while temperate counterparts lag behind

Responses to rising temperatures vary by latitude, but researchers fear there may be no clear winners among these strategies

A team of scientists from the University of British Columbia, the University of California, Santa Cruz, and the University of Miami published a new study in Ecology Letters showing how rising temperatures resulting from climate change are affecting where plants and animals can live in mountain regions around the globe.

The researchers found that tropical species are shifting their ranges up mountain slopes at a rate that’s 2.1 to 2.4 times faster than their temperate counterparts, and tropical forests, in particular, are undergoing these changes 10 times faster than temperate forests. These findings contribute new insight into how species survival outcomes—and potential conservation strategies—may vary by geography as our world warms.

Members of the research team each brought their own expertise in studying these types of changes within plant and animal communities. Lead author Benjamin Freeman, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of British Columbia, had documented the shifting ranges of birds and other animals in mountainous regions of the tropics. Meanwhile, coauthor Kai Zhu, a UC Santa Cruz assistant professor of environmental studies, had been researching the effects of climate change on North American forests. And coauthor Kenneth Feeley, and associate professor of biology at the University of Miami, had extensively studied the biogeography of tropical forests.

With help from UC Santa Cruz environmental studies graduate student and coauthor Yiluan Song, the team set out to combine their insights into a new global perspective. They analyzed data from forest surveys in mountainous regions in North, Central, and South America, as well as worldwide findings from 93 prior studies covering thousands of plant and animal species in mountain environments. Their goal was to get a sense of how species were responding to rising temperatures.

Climate change threatens biological diversity across the planet in part because temperature is one of the environmental conditions that defines the geographic range of appropriate habitats for each species. And the rate of warming resulting from human-driven climate change is faster than many plants and animals can adapt. So for some species, migrating to cooler regions may be the best chance for survival.

“Basically, species can tolerate these changes through adaptation or acclimation or, alternatively, they can shift their geographic distributions to minimize the climatic changes they experience,” Kenneth Feeley explained. “If they fail to do either of these things, then eventually they will suffer and be at risk of extinction.”

For those species seeking colder temperatures on land, there are two main options. Plants and animals can either move great distances in latitude—away from the equator and toward the poles, where the sun’s energy is less intense—or, in mountainous regions, they can make much smaller shifts upward in elevation, where the thinner atmosphere helps to keep things cooler.

Not all species can successfully make these migrations. In fact, prior research by Kai Zhu had shown a “failure to migrate” in North American forests, where young trees did not seem to be establishing themselves in cooler habitats farther north. The new paper shows that, in mountain regions, temperate forests are fairing slightly better at making smaller upslope migrations. But these shifts still lag far behind the rate of warming.

“We know from observation that we have seen substantial warming already, but what we don’t see is responsiveness from temperate forest ecosystems,” Zhu said. “So that raises concern.”

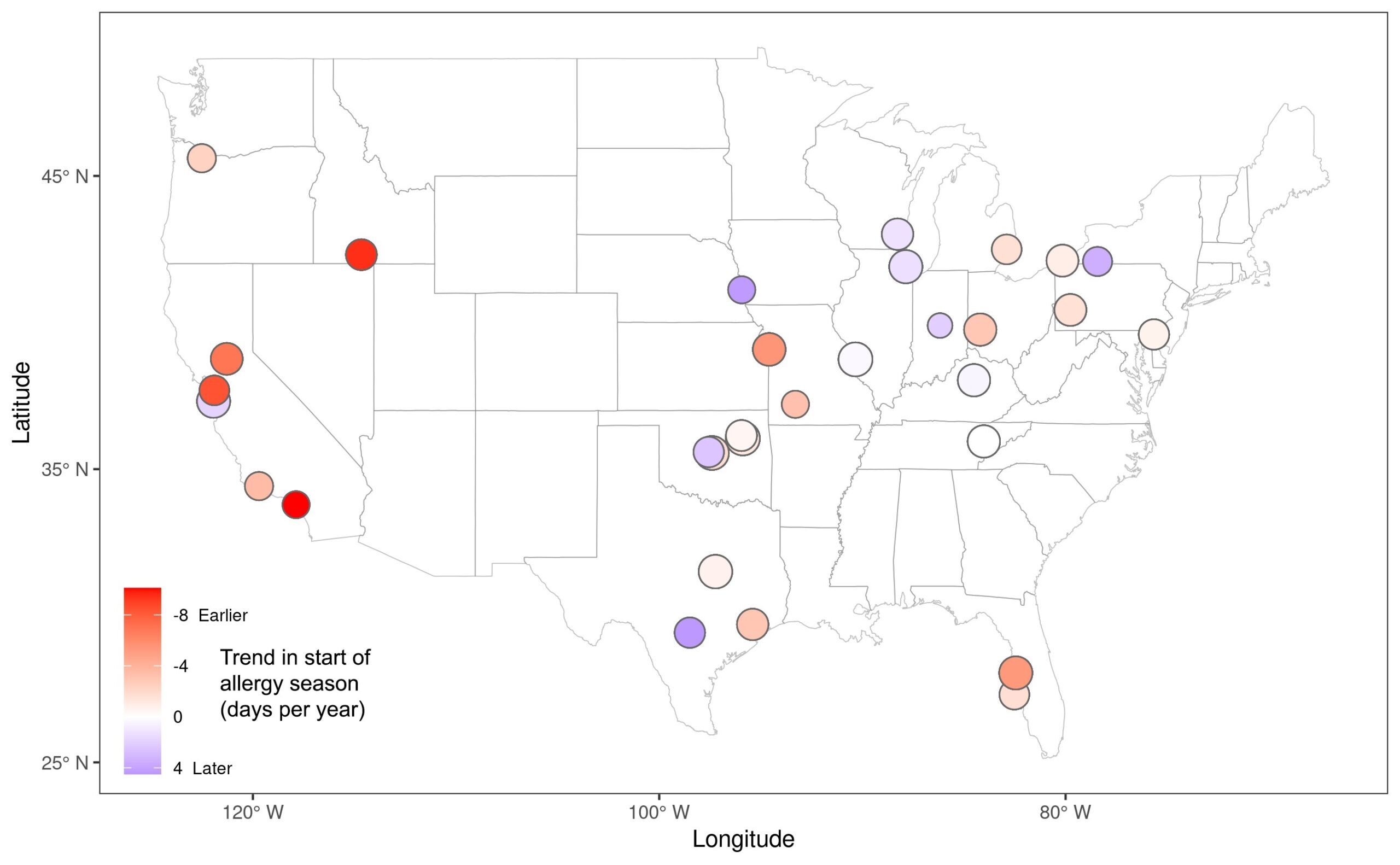

The study says it’s possible that temperate zone species may have more ability to respond to climate change by shifting the timing of seasonal life processes—like blooming or shedding leaves for plants and hibernation or seasonal migration for animals—rather than shifting in space. But it’s unclear if this strategy will be able to keep pace with changes in the environment as warming continues.

Meanwhile, higher rates of migration in the tropics might not necessarily be a good thing either. Benjamin Freeman’s prior work had shown that tropical birds are going all-in on the strategy of migrating upslope, and he was concerned to see this same trend in other species within the new paper.

“In the tropics, these species really are zooming uphill as it gets warmer, and in the short term, that’s great because it means that they’re able to respond,” he explained. “But the problem is that mountains aren’t infinitely tall. Species can’t just keep shifting up forever because they’re going to run into the top of the mountain. It’s really like they’re on an escalator to extinction.”

And, as Freeman and his coauthors point out in the paper, that process seems to run much faster in the tropics, despite the fact that the magnitude of recent warming has actually been greater in temperate regions. One theory that might explain these findings is that tropical species may be more sensitive to changes in temperature than their temperate counterparts, perhaps because seasonal variability is limited in the tropics.

But regardless of the cause, the paper’s authors see this trend as a major conservation threat. After all, the tropics are a global hotspot of biological diversity, and tropical mountains, in particular, support the greatest number of species. There are conservation steps that could help tropical mountain species in the near term—like preserving habitat corridors to aid upslope migration—but ultimately, the most meaningful action we can take to protect tropical and temperate species alike will be to slow the rate of global warming.