From: Michigan News

New paper: Wu R, Song Y, Head JR, Katz DS, Peay KG, Shedden K, Zhu K (2025) Fungal spore seasons advanced across the US over two decades of climate change. GeoHealth, 9, e2024GH001323. https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GH001323

A first-of-its-kind study led by the University of Michigan has ‘implications for both ecosystem processes and human health’

Although many of us spend allergy season cursing out plant pollen, spores from mold and other fungi also deserve some of that same disdain. These invisibly small agitators tend to fly under the radar, despite being capable of causing the same sneezes, sniffles and, in some cases, severe respiratory issues.

And these stealthy allergens are sneaking up on us earlier than ever before, according to new research led by the University of Michigan and published in the journal GeoHealth.

“Over the past two decades, fungal spore seasons in the U.S. have shifted significantly due to climate change. This has implications for both ecosystem processes and human health,” said Ruoyu Wu, a leader of the research project while earning her master’s degree at the U-M School for Environment and Sustainability. She is now pursuing her doctoral degree at the University of Florida.

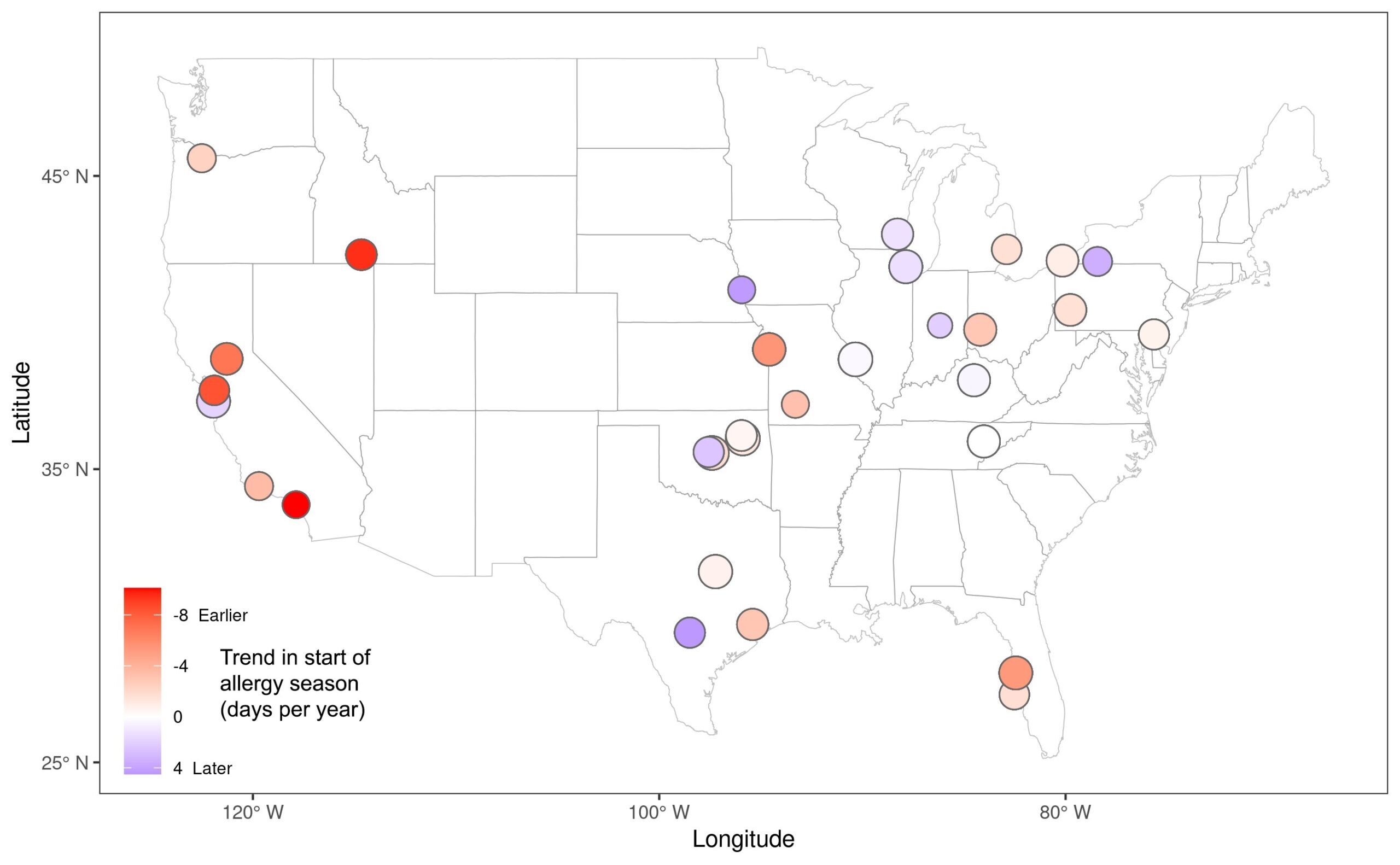

Against a backdrop of changing temperatures and precipitation patterns, Wu and her colleagues performed the first large-scale systematic study of outdoor fungal spore abundance across the continental United States between 2003 and 2022. This was made possible by data collected at 55 pollen counting stations associated with the U.S. National Allergy Bureau.

The researchers found that, on average, spore allergy season was kicking off 22 days earlier in 2022 than it had been in 2003.

“This is the first time that we’ve been able to show that the fungal spore seasons have changed, and the change is pretty big. That’s three weeks over the past two decades,” said study senior author Kai Zhu, U-M associate professor of sustainability and environment and of ecology and evolutionary biology.

A 2023 epidemiological study found that, out of clinical samples collected from more than 1.6 million patients in the U.S., roughly 1 in 5 showed signs of sensitivity to fungal allergens.

That means folks who have suspected their respiratory distress is creeping up in the calendar likely aren’t imagining things and may want to start their remedies sooner, the researchers said. This finding is also important for doctors and health care professionals who offer guidance to patients and the public on preparations for allergy season.

“We also know that buildings and vegetation are huge sources of fungal spores in the air,” said Yiluan Song, another leader of the study and a postdoctoral fellow at the Michigan Institute for Data and AI in Society. That means another practical action item, beyond people preparing earlier for the “natural” spore season, is alleviating and preventing mold in our built environments.

In addition to its public health implications, the study also revealed ecological concerns. Beyond looking at when spore concentrations reached a threshold that would trigger allergic reactions in people, the team also examined a flexible threshold based on the accumulated spore count in the year, which might be more relevant to the timing of fungal reproduction.

Through the lens of that ecological threshold, the team still observed a season shift in spore season: Ecological spore season starts an average of 11 days earlier in 2022 across the U.S. compared with 2003.

Nevertheless, the study found that the accumulated spore count declined over the survey period. Spores are microscopic particles that fungi use to reproduce and fungi are a vital link in many of nature’s food webs, as both a food source and decomposers of organic material. As climate change affects the production of these tiny organisms, it could have outsize impacts on broader ecosystems.

It appears that warming temperatures are driving the advance of spore season, while drought conditions may be responsible for decreasing spore production, Song said.

“Here, we see a very visible fingerprint of climate change,” she said. “So another key action item is to try to curb climate change.”

Collaborators at U-M included Jennifer Head, assistant professor of epidemiology, and Kerby Shedden, professor of statistics. Daniel Katz, assistant professor at Cornell University, and Kabir Peay, professor at Stanford University, also contributed to the study. The research was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation, the U.S Department of Energy, Michigan Institute for Data and AI in Society, and the Schmidt Sciences program.